Go to https://julialang.org/downloads and download the latest stable release (v1.8.2, as of 1/2/23, but any 1.8.x should work cleanly with the homework and notebook environments) for your operating system. Install Julia using the downloaded file.

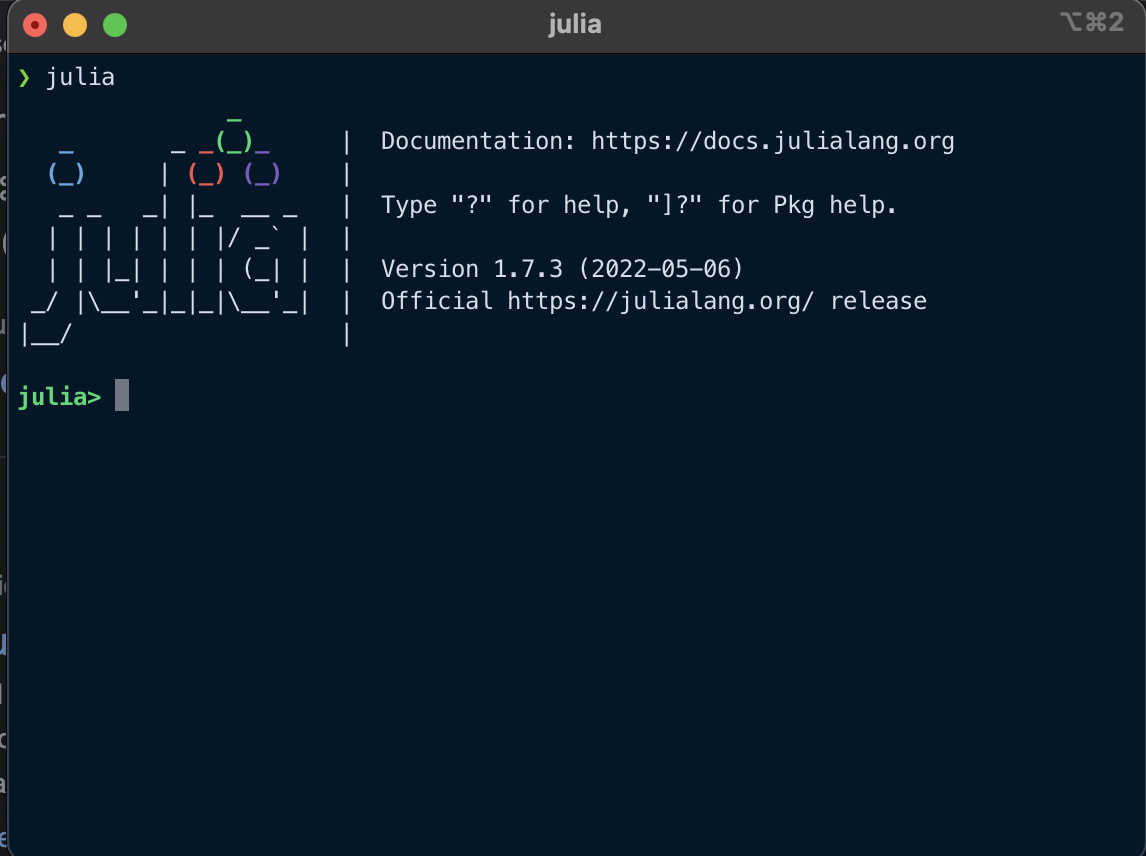

After installing, make sure that you can run Julia. You may have a "Julia 1.8" program on your computer, or you can run the command julia in a command line. Either way, you should see a window (or terminal) like the following:

This is called the Julia REPL, which is the primary environment for interactively executing Julia commands. Make sure that you can execute

This is called the Julia REPL, which is the primary environment for interactively executing Julia commands. Make sure that you can execute 1+1.

PkgThe next step is to become familiar with Julia's package manager, Pkg. We will use Pkg to install packages which can then be loaded and used in the REPL or in Julia code. There are two ways to load Pkg:

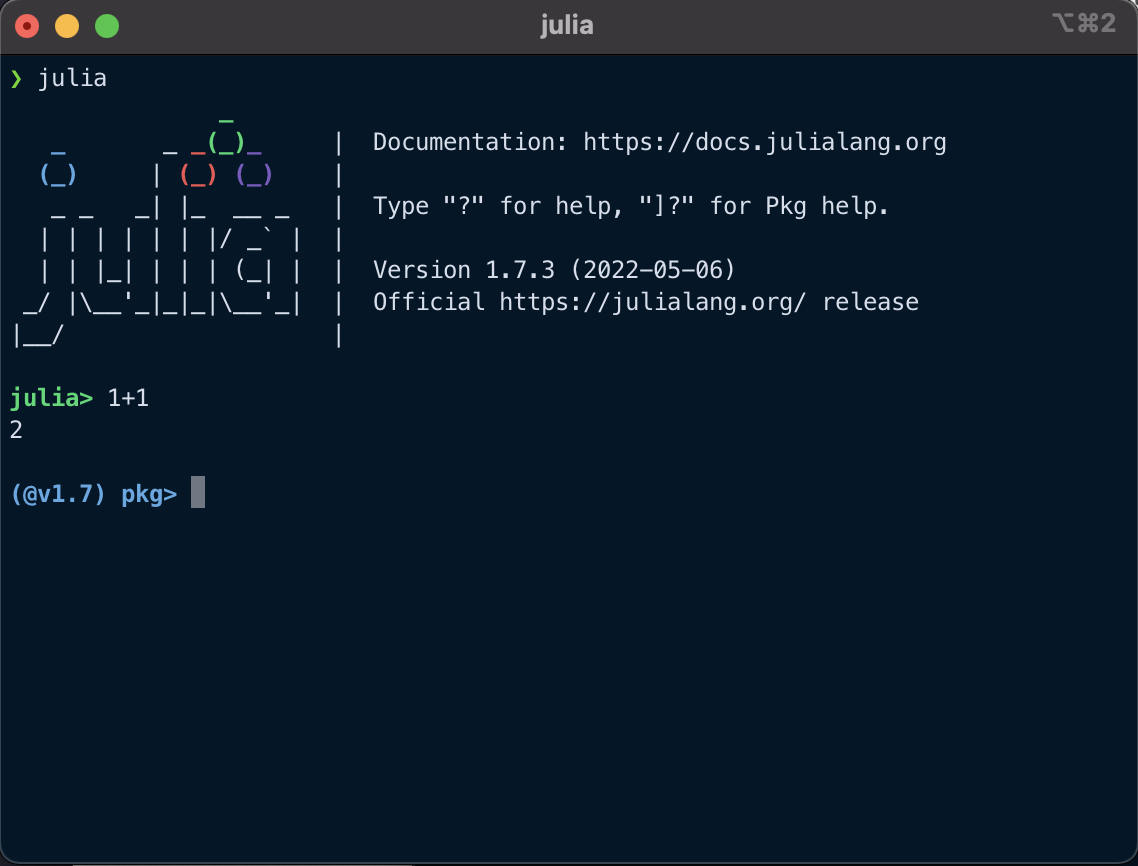

From the julia> REPL prompt, enter ] to switch from Julia mode to Pkg mode:

In a script, use import Pkg (typically at the start of your file).

With Pkg, packages are managed within environments, which are independent sets of packages associated with a location or a project, like other package managers such as conda or virtualenv. When packages are added or updated, Julia will only update dependencies within a given environment, so different versions of packages can be used for different projects. Unlike conda, which keeps separate installations for each environment, each version of each package is installed in a single location (which can then be accessed by multiple environments), which reduces storage space use.

Each environment has two files which specify required packages: Project.toml and Manifest.toml. The combination of these two files allows for complete reproduction of the package environment. We will provide these files for any homework assignment or in-class exercise to ensure compatibility, but if you make changes, you should commit and push them. If you upgrade your Julia version and run into a problem, you can delete Manifest.toml and re-create it.

The default environment is the "central" environment for your Julia version, which in this case is v1.7 (as reflected by the (@v1.7) pkg> prompt in the screenshot above. This environment will be used any time you load Julia and start evaluating code without actively selecting a new environment. To create a new environment or load an existing one, use activate <environment directory>, where <environment directory> is the location of the relevant Project.toml. For example,

(v1.7) pkg> activate .will activate an environment in the current working directory (loading one if it exists or creating a new one if it does not). This will change the prompt to reflect the active environment. For example,

(v1.7) pkg> activate tutorial

(tutorial) pkg>shows that the environment in the tutorial/ directory has been activated.

The equivalent command for Julia code is Pkg.activate(), so you might see the following at the top of a file:

import Pkg

Pkg.activate(".") # activate an environment in the current working directoryTo add packages to an environment, use add:

(@v1.7) pkg> activate tutorial

(tutorial) pkg> add PlotsPkg will then install and pre-compile any needed dependencies. Similarly, to remove packages, use rm.

After using Pkg.activate to load an environment, you may want to make sure that the correct versions of each of the packages are installed (based on the Project.toml). This is done using Pkg.instantiate():

(v1.7) pkg> activate tutorial

(tutorial) pkg> instantiateor, at the start of a file,

import Pkg

Pkg.activate(".") # activate an environment in the current working directory

Pkg.instantiate() # install any needed package versionsIf all listed package versions are installed, Pkg.instantiate() will return nothing. If there is no Manifest.toml associated with the project directory (if it was deleted or you only started with a Project.toml), it will be created using this step.

Once the environment has been activated, you can load and use any packages. The primary command is using, as in

using Plots # load Plots.jl for useYou can also load multiple packages at once,

using Plots, DataFramesthough you may want to minimize this, as it can get unreadable quickly.

Good form is to load all relevant packages at the beginning of the file, but you can load packages as needed later if you only use those commands in a particular section of your code.

Git is an industry standard version control system. It allows you to keep track of changes to files. This means that you can document changes and bug fixes, revert changes that created problems, and create alternative pathways to test changes which can then be incorporated into the main file(s) if desired. GitHub is a commonly used remote repository which ties into git. Remote repositories allow version-controlled software to be backed up and shared.

If you don't have one, you should create an account at GitHub, ideally linked to your Cornell email (though if you have a pre-existing GitHub account, you can use it). It will be easiest if your username includes your name or NetID in some way, but it's not necessary. You should also install git if your computer does not have it (which you can test by typing git at a command line).

You can interact with GitHub either through the command line (using a terminal) or GitHub Desktop.

Next, you should create a folder for the course, something like bee-4750/. You could create a lectures/ subfolder in here for notes, but we're mostly interested in storing homework files.

Git: A software version control system. For an introduction to Git, see these CodeRefinery tutorials.

Repository: A database storing and tracking the files and folders associated with a particular project. A local repository is hosted on a specific, locally-accessed machine, while a remote repository is hosted and accessible on a server. Remote repositories can be private if they are accessible only by certain users or public if they can be seen and accessed by anyone.

Commit: A commit consists of a tracked change to a file or a set of files. When you make a commit using git commit, Git creates a unique ID associated with the state of the files in the repository at that point. This allows you to track how files have changed and use or revert back to a previous state. As a result, it is a good idea to make frequent commits which respond to small code changes (like adding a new feature or fixing a specific bug). Files are added to a commit using git add <files>, which can be used multiple times for a given commit. Commits are typically associated with a message briefly describing what changes were made, using git commit -m "<commit-message>"

GitHub: A cloud-based service for remote management and storage of git repositories.

Clone: A clone is a copy of a remote repository on your local system. A clone allows you to make changes to the files in the local version of the repository and keep track of those changes using Git. These changes can later be "pushed" to the remote repository. You can clone a remote repository to which you have access using git clone <remote-repository-url>.

Push: Changes to a local repository are sent to the remote repository using git push. Errors when pushing are usually the result of misalignments between the local and remote repository histories; a Google search can usually identify the specific cause.

Pull: Pulling is the opposite of pushing; a git pull updates the local repository to reflect changes to the remote repository. To minimize the risk of push errors for simple projects (where it's unlikely that too many people are making substantial changes), it's a good idea to pull before you start to make local changes.

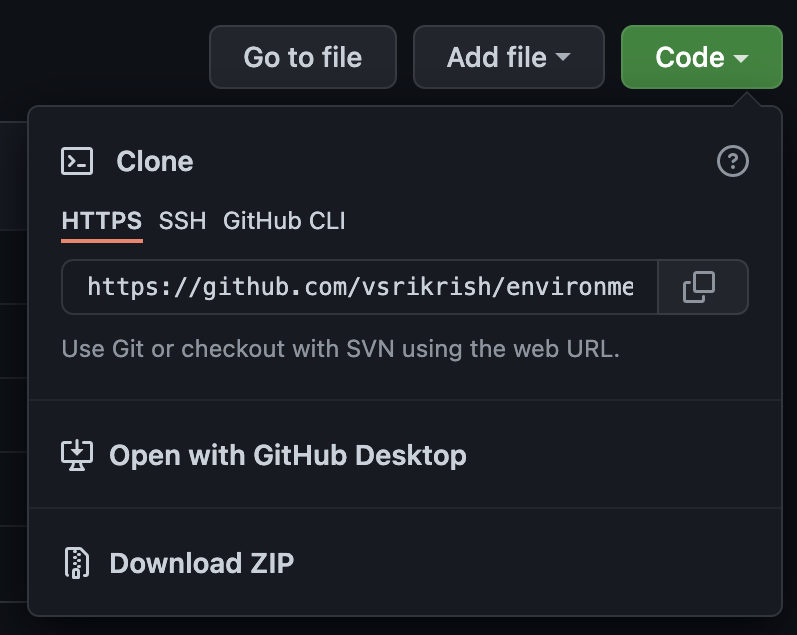

When you open a repository URL in your browser, there are several tabs; the default tab is "Code". That's the main tab you'll use, though you can use "Issues" to request code help from the instructional staff or "Actions" to see whether your report has successfully been compiled (or if it's failed, why). The "Code" tab includes a link to the commit history of the repository, which will give you the unique IDs associated with previous commits if you want to roll back any changes.

An important button is the green "Code" button. Clicking on this will give you the URL to use when you clone the repository.

If you have SSH set up to work with GitHub (which is not necessary here, but is generally a good idea for security's sake), you can use the SSH address; otherwise, use the HTTPS address.

Finally, in the "Code" tab is a view of the repository structure, including folders and files. You can click on those links to view the code without having to clone the entire repository.

The README for the repository (generated from the repository's README.md file) is also included. This will contain an overview of the assignment, a list of packages included in the provided environment, and instructions on how to compile your report (which you may not need after the first couple of assignments).

The instructions in this section and below assume that you're interacting with Git and GitHub using your system's command line. If you use a tool with a graphical interface, please familiarize yourself with the specifics for that application.

To clone your repository, navigate to a parent directory where the local repositories for this class will live. For example, if you have a classes/ directory for your schoolwork, you could create a BEE 4750 subdirectory from within this directory using mkdir BEE4750. Then navigate to this directory with cd BEE4750. You don't need to manually create a directory for each assignment; this will be automatically done when you clone the remote repository. The clone command will be something like

git clone <repository-clone-url> <local-folder-name>The local-folder-name is an optional argument; if you leave it off, it will use the same name as the repository. This might be a bit clunky due to the naming conventions of GitHub Classroom, and you might want to simplify it to just be hw0 or hw1 or some such. This will then create local copies of all the folders and files in the repository within local-folder-name/, which you can then start editing. It will also automatically set up the remote repository as the default remote repository for the local repository, so no further configuration is needed.

git status is a useful command to use to see what files are different from the remote repository. It will also show you which files Git is not tracking, which you may or may not want to add to the repository. You can use git ignore to make git status ignore any files or classes of files that you would never like to track.

Once you have made some changes to your local repository, it's a good idea to make a commit so that the state of the repository is saved (in case further changes break something). A good commit has a few characteristics. It should be small; each commit should correspond to a coherent change like the addition of a new "feature" or a bug fix. This makes it easy to go back to a previous state where things were known to work. When too many changes are made within a single commit, it may not be clear what worked or didn't work at that state or what might be lost by rolling back to a previous commit. It's a good idea, for example, to make a commit whenever you make a first attempt at solving a problem; you can then make subsequent commits as you make edits or fix bugs. Commits are associated with brief "commit messages" which describe the changes made in that commit; make these short but informative!

If you have only changed a few files and want all of those changes added to the commit, you can use

git commit -am "Commit Message"Otherwise, if you want to select only specific files for a particular commit, you can break this into two commands:

git add <files>

git commit -m "Commit Message"where git add can be used as many times as needed to add all of the relevant files.

After each commit (or after a few commits), you should push your changes to the remote repository to keep things synced. You do this with a git push command. If this is successful, the remote repository view will be updated with the commits that you pushed and the new state of the repository.